In a bid to stabilise prices and aid the textile industry, the Centre has exempted import duties on raw cotton until December 31, 2025. Though intended to provide cheaper raw material for mills, the move comes when market prices of cotton have remained below the Minimum Support Price (MSP) since October 2023, eroding farmer income.

Removing import duty in such a situation will further hurt the 58 lakh farmers cultivating about 130 lakh hectares of cotton who are already in distress. The key question is whether the government should prioritise cheaper yarn for textile mills at the expense of millions of cultivators.

Evolution in cotton cultivation

Cotton, cultivated for centuries, has been as one of India’s most important commercial crops. The area under cotton rose from 76 lakh hectares (lha) in 1960-61 to about 127 lha in 2023-24, making India the world’s largest cultivator with nearly 37 per cent of the global area. Yet, the story is not uniform across States. Maharashtra, Gujarat and Telangana together account for about 70 per cent of India’s cotton acreage, while States such as Tamil Nadu, despite being home to a large textile industry, have witnessed a sharp decline in cultivation from 3.96 lha in 1960-61 to 1.30 lha in 2023-24.

India’s productivity levels, however, remain dismal. Yield rose from 152 kg/ha in 1980-81 to only 190 kg/ha in 2000-01, far below global averages. It was only after the introduction of Bt cotton in 2002 that production surged. Between 2002-03 and 2023-24, the cotton area increased from 77 to 127 lha, while production rose dramatically from 86 lakh bales to 325 lakh bales (one bale = 170 kg). This transformation made India the world’s largest producer of cotton. But, has this revolution translated into better income for farmers?

Unremunerative crop

Cotton cultivation is unlike most other crops, marked by high risks and costs. First, nearly 70 per cent of cotton area is rainfed, leading to unstable yields. Second, pest infestations, particularly bollworm, remain a constant threat, pushing up pesticide use and costs, even after the introduction of Bt cotton.

Third, unlike wheat or paddy, cotton picking is labour-intensive and entirely manual, adding a significant burden to the cost of cultivation.

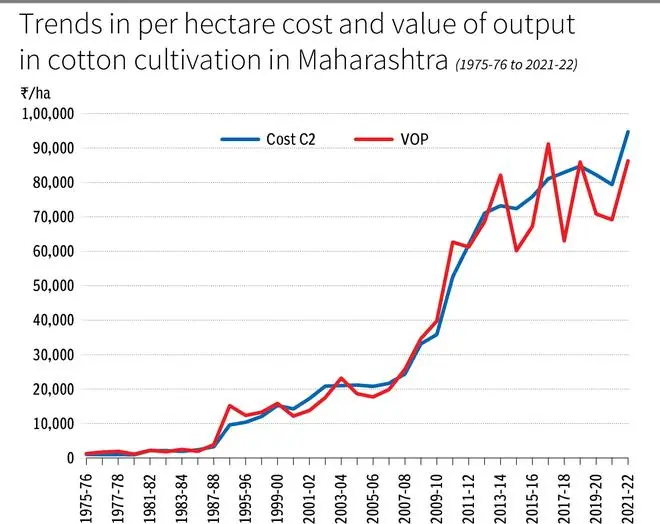

The cost and income numbers reveal the gravity of the problem. Data from the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) show that per hectare C2 cost (which includes all the expenses incurred for crop cultivation including a fixed cost component) has increased many-fold. In Maharashtra, which accounts for one-third of India’s cotton area, costs rose from ₹14,234/ha in 2000-01 to ₹94,710/ha in 2021-22 and in Tamil Nadu, they skyrocketed from ₹28,149 to ₹1,24,493.

The value of production (VOP) too increased but not proportionately. In Maharashtra, VOP per hectare rose from ₹12,148 in 2000-01 to ₹86,267 in 2021-22, but the cost escalation outpaced income growth most of time (see, Figure 1). In Tamil Nadu, where farmers cultivate cotton largely under irrigated condition, suffered losses in 14 out of 15 years (data was not available for some years) from 2000-01 to 2021-22. This has been the story in all the leading cotton producing States.

The primary reason for the losses is that cotton farmers have seldom received market prices on par with the MSP. According to CACP data, between October 2020 and January 2025, cotton prices in the open market remained below the MSP for most of the period due to reduced procurement. Therefore, any policy move that further lowers farm-gate prices such as duty-free imports will only deepen farmers’ losses.

Unjustifiable demand

The textile industry has been vocal in demanding measures such as removal of import duty, curbs on exports and even delisting cotton from futures trade to bring down yarn prices. But are these demands reasonable? When cotton prices had been stagnant for years, industry players did not lobby for farmer welfare.

On the contrary, when cotton prices finally began rising marginally due to a post-Covid rebound in global demand, the call for suppressing them grew louder. Similarly, restricting exports ignores the fact that India’s cotton farmers depend on global demand to realise better prices in years of surplus.

The current duty exemption on imports, while benefiting textile mills, will hurt farmers by dragging down already weak domestic prices. Farmers’ associations in Tamil Nadu argue that the removal of import duty on cotton could reduce market prices by up to ₹2,000 per quintal, causing farmers a potential loss of around ₹30,000 per acre. If the government continues to prioritise mill owners over cultivators, cotton acreage may shrink further, jeopardising long-term raw material security for the textile sector itself.

Tamil Nadu is already a striking example, where area under cotton declined by over 2.66 lakh hectares between 1960-61 and 2023-24, precisely because farmers found it economically unviable.

To conclude, the case of cotton underscores the deep structural imbalance in India’s agricultural economy — while industries demand cheap raw materials, farmers are seldom assured of remunerative returns. The government’s recent decision to exempt customs duty on cotton imports may temporarily comfort textile mills, but it risks driving millions of cultivators further into distress. During the last five years alone, cotton area declined by about 22 lha.

What is needed is not ad-hoc measures that favour one segment of the value chain, but a comprehensive long-term policy that guarantees fair farm-gate prices through stronger MSP procurement, reduction in input costs and effective risk-mitigation mechanisms.

Until import duties are restored, the government should at least provide adequate production subsidies to offset farmers’ losses. If such safeguards are ignored, the gradual decline of cotton cultivation will not only devastate farm livelihoods but eventually undermine the very textile industry that today seeks relief at their expense.

The writer is former full-time Member (Official), Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices, New Delhi. Views expressed are personal

Published on September 2, 2025